History

of

History

of

Sedentary Agriculture

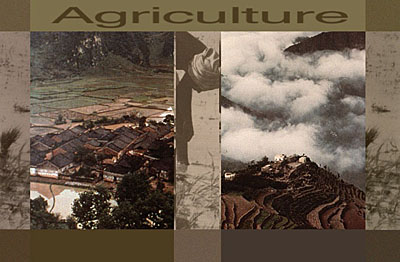

While

they are not exciting in appearance, settled agricultural villages like this

early example at Ban Po, China (left), represented a radically new way of life

for human beings, unlike anything that had existed before.

While

they are not exciting in appearance, settled agricultural villages like this

early example at Ban Po, China (left), represented a radically new way of life

for human beings, unlike anything that had existed before.

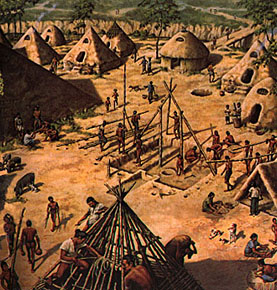

First, agriculture means sedentism--living permanently in one place. This was itself new to human beings, and it may have seemed very constraining to the first people to experience this way of life. Living in one spot permanently means exploiting a relatively small amount of land very intensively (rather than exploiting a large amount of land extensively, as hunter-gatherers did), and over a long period of time.

To understand how radical this change was, it is necessary

to consider carefully both the advantages and disadvantages of gaining one's

living from one piece of ground and the effects of such a way of life on the

environment.

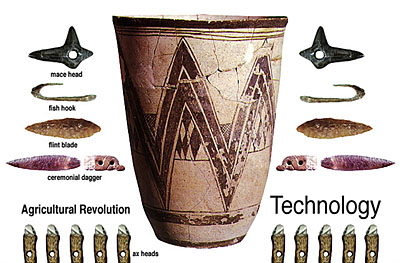

Emergence of Technology Necessary for Agriculture

|

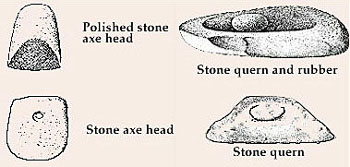

Surprisingly, this dramatically new way of life was not very dependent on new

technology. On the contrary, in the earliest phase of development, pioneer

farmers used techniques and tools which had long been familiar to

hunter-gatherers: the stone axe, hoe, and sickle (left) for preparation of the

fields and harvesting the grain. The primitive milling device for grinding seeds

between two stones (the "quern," below) to process the grain into edible form

had been in use for thousands of years by peoples who collected seeds but did

not plant them.

Surprisingly, this dramatically new way of life was not very dependent on new

technology. On the contrary, in the earliest phase of development, pioneer

farmers used techniques and tools which had long been familiar to

hunter-gatherers: the stone axe, hoe, and sickle (left) for preparation of the

fields and harvesting the grain. The primitive milling device for grinding seeds

between two stones (the "quern," below) to process the grain into edible form

had been in use for thousands of years by peoples who collected seeds but did

not plant them.

Profound cultural rather than

technological changes were necessary at first to permit adaptation to the new

mode of life. But once the shift had occurred, ever more changes, both cultural

and technological, became possible.

Preparing the Seed-Bed

To agriculturalists, survival is dependent upon getting the seeds--such as the

wheat grains shown above--to sprout and grow in the soil. Originally fields were

cleared of weeds and prepared for planting by hand at great effort, using

primitive hoes or digging sticks.

The invention of the scratch plow in Mesopotamia about 6,000 years ago was a

great labor-saving device for humans. It also marked a revolutionary stage in

human development--the beginning of systematic substitution of other forms of

energy, in this case animal power, for human muscles.

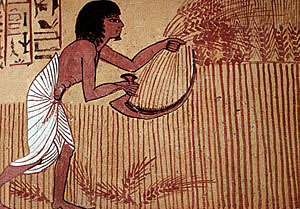

The techniques for gathering or harvesting cereal crops, shown left in a tomb

painting of New Kingdom Egypt and below right in photograph of a modern Egyptian

farmer, remind us how precious a commodity grain was to early civilizations.

Grain was dearly bought with human sweat and diligence and strict social

organization. Most cultures quite naturally came to associate the main crops

that sustained their existence with the substance of life itself, either

worshipping those plants or seeing them as symbols of the power of life.

The techniques for gathering or harvesting cereal crops, shown left in a tomb

painting of New Kingdom Egypt and below right in photograph of a modern Egyptian

farmer, remind us how precious a commodity grain was to early civilizations.

Grain was dearly bought with human sweat and diligence and strict social

organization. Most cultures quite naturally came to associate the main crops

that sustained their existence with the substance of life itself, either

worshipping those plants or seeing them as symbols of the power of life.

The precariousness of hard-won wealth in grain is difficult for many modern

people to understand. We are separated from the material base of our culture by

the complex nature of our way of life and so cannot see it easily. But for the

ancients (as for most developing nations today), both the source of the

community's livelihood and the slim margin between life and death were quite

visible.

The precariousness of hard-won wealth in grain is difficult for many modern

people to understand. We are separated from the material base of our culture by

the complex nature of our way of life and so cannot see it easily. But for the

ancients (as for most developing nations today), both the source of the

community's livelihood and the slim margin between life and death were quite

visible.

There is only a short period of time each year in harvest

season in which to reap the grain; wet weather at the wrong time can spoil the

crop; social disorder at planting or harvest time may mean famine. In addition,

once harvested, the grain must be stored and protected against dampness, against

vermin such as rats and mice, insects, mold and fungi. And if that were not

problem enough, stored grain easily becomes stolen grain, so it must always be

protected against thieves and enemy raiders. In this way, wealth brought with it

"security problems" which had not existed before.

To live by exploiting grain crops, humans must process the grain before it can

be eaten. Human teeth, jaws, and digestive tract are simply not adapted for this

kind of diet. The typically human solution to this problem is, however, not to

evolve biologically, but to find cultural or technical solutions to problems: in

this case, to develop the knowledge and techniques for processing grain.

To live by exploiting grain crops, humans must process the grain before it can

be eaten. Human teeth, jaws, and digestive tract are simply not adapted for this

kind of diet. The typically human solution to this problem is, however, not to

evolve biologically, but to find cultural or technical solutions to problems: in

this case, to develop the knowledge and techniques for processing grain.

One early and universal technique of transforming grain into food is to mill the seeds slightly between two stones and then to boil the grain in water, making a kind of gruel. If ground into coarse meal, boiling in water will produce something like the oatmeal we still eat at breakfast. If ground fine and mixed with water into a paste and then baked, the grain is transformed into bread. The yeast cultures which leaven some forms of bread are naturally occuring, but were regarded as magical prior to the relatively recent discovery of micro-organisms.

If stored grain gets wet and begins to sprout, the stored

carbohydrates in the seed begin converting into sugar. While the grain is

spoiled for bread-making, it can still be consumed if treated in another process

called fermentation. The sprouted grain is first baked, ground into a paste

(called malt), and then added to water. With the right yeast and little luck,

the result is beer, another of the food inventions of early agriculturalists.

Technological Specialization

Over time, the settled way of life gives birth to many crafts and skills and special forms of knowledge. The economic functions that individuals once were required to master in order to survive are carried on at a higher level of skill by groups of specialists, who exchange their labor or their products for grain or other commodities and eventually for money.

The specializations are almost endless--and, in fact, they continue to proliferate in our own times. The earliest were: baking, brewing, weaving, dyeing, carpentry, pottery-making, stone and metal-working, etc. Needs arise for merchants and soldiers and artists. Priests or shamans and healers had probably existed in the earlier hunter-gatherer societies, but knowledge of writing gave rise to a host of new specializations: estate or temple managers, literate bureaucrats, calendar-keepers, professional medical practitioners and teachers.

As technological specializations accumulated, the sum total of knowledge in the community soon exceeded the capacity of any individual mind. Specialized forms of knowledge were no longer sharable throughout the community, but instead became the "property" of special groups. The social egalitarianism of hunter-gatherer bands was very difficult to maintain in these new circumstances